Introduction

I began my professional journey training athletes in 1980, and in the 1980s was also personally involved in competitive strength sports. At that time there were a number of burning questions I had about training including questions about optimal speed of movement in strength exercises

I was not satisfied conducting the speed of movement in strength training aimlessly, or worse, in a way simply to allow myself to lift more weight. I witnessed ample examples of both around me every day. I wanted more purpose, a better understanding, a pursuit of excellence to optimize training for myself and those whose training I was responsible for.

I set out on a journey of discovery. Very little information was available. So I formed my own theories and methods, and set about testing them for over a decade before discussing them publicly.

I had no desire or intention to market or expose the concept. I developed it to serve the athletes as best as I could. Nor did I anticipate the extent to which this concept would travel globally, or how its origin and intent would be misinterpreted.

The purpose of this article is to share the journey of the concepts and methods I developed and refined in the area of Speed and Movement (SOM) and Time Under Tension (TUT). In doing so I provide those historical clarity for those who value accuracy of information and history.

What is Speed of Movement?

So, what is Speed of Movement in strength training? I have summarized the answer to this question in my 1998 text, How to Write Strength Training Programs:

Speed of movement in strength training refers to the rate at which the external resistance or body is moved. Another word commonly seen in North American literature is tempo. I am not sure whether this is a typical North American word or an attempt to mimic European terminology. Speed of movement can be measured in various ways including

- Angular velocity (degrees per second).

- Meters per second.

- Number of seconds per contraction phase.

- Angular velocity: Is suited for comparison to measurements made in clinical settings e.g., the Cybex and Kingcom devices have settings that are measured in degrees per second. However I have not found this a practical method in the field.

- Meters per second: Is suited for comparison to movement speed e.g. running speed, which is more measurable and has greater application than the measurement unit of angular velocity for the practitioner. However it is still difficult to measure in the gym and convey to the trainee.

iii. Number of seconds per contraction phase: I believe is the easiest and most applicable to the practical environment of strength training. During the early 1980’s I noticed Ellington Darden (an American strength expert writing for Nautilus) write about number of seconds the eccentric and concentric contractions should take to complete on the Nautilus machines. By the mid 1980’s I had developed a system of denoting and communicating speed of movement in strength training that involved a simple numbering system. [1]

What were the dominant paradigms about Speed of Movement (SOM) in strength training in the early 1980s?

My search for the answers to my questions about speed of movement led me to the teaching of a few, the only ones I could find in the early 1980s who addressed this topic. I documented these findings in earlier writings:

During the early 1980’s I noticed Ellington Darden (an American strength expert writing for Nautilus) write about number of seconds the eccentric and concentric contractions should take to complete on the Nautilus machines. [2]

I was first influenced by Arthur Jones and Ellington Darden. They were the first I had seen to attach numbers to training programs.[3]

They advocated for a controlled speed of approximately 3 seconds lowering (eccentric) and 1-2 seconds lift (concentric). The dominant message was that the eccentric phase should take longer than the concentric phase. There was no reference to the variable of the pause, the duration between the two muscle contraction phases.

I acknowledged that Jones and Darden were predominantly coming from a bodybuilding perspective. At the same time, I noted that track and field athletes and coaches at the highest level advocated all strength movements be executed explosively and with no pause. I can remember watching a national representative throwing athlete performing barbell pullovers at the Australian Institute of Sport, very concerned that his shoulder was to about to dislocate.

There was no common ground or agreement – it was either controlled speed movements for bodybuilders or explosive movements for power athletes.

Whilst I appreciated their respective influences, I felt a number of elements missing. This left me asking the following questions:

- What if we applied a pause between the contraction phases?

- What if we used various speeds for different exercises or different training outcomes? g., could there be a time for a bodybuilder to lift explosively, or a power athlete to lift slowly?

- What if we varied the pause duration for different exercises or different training outcomes?

These questions may seem redundant now, however in the early 1980s they were pertinent, because no-one that I had found was addressing these three questions.

So, I created my own theories and methods about Speed of Movement.

What difference does the pause between the eccentric and concentric phases make in strength training adaptations?

When I began competing in strength sports the role of the pause became blatantly clear, at least to myself. I was stunned by the implications of the pause on the chest during the bench press. A competitive powerlifter is required to pause the bar on the chest until the referee signals to commence the concentric (lift) phase. The duration of the pause was subjective. Some held the pause shorter, some longer. The duration of the pause had significant implications on how much weight you could displace successfully and be given green lights by the judges (a successful attempt).

I had developed an awareness of the pause or isometric contraction between the eccentric and concentric contractions. This was intuition, a gut feeling… [4]

I was also surprised that no-one in that era was considering the role of the pause in not only load displacement, but on the training effect.

In forming my position in relation to the pause, questions that I had included:

- What’s the difference between an exercise that commences with the eccentric contraction and a movement that commences with the concentric contraction?

- What is the purpose of the pause?

- When should I pause?

- How long should I pause for?

- What happens if I vary the pause?

1. What’s the difference between an exercise that commences with the eccentric contraction and a movement that commences with the concentric contraction?

I recognized that you could divide lifts into two categories based on the muscle contraction involved first. For example, when conducting pushing movements such as bench press and shoulder press, one typically commences with the eccentric phase. When conducting pulling movements such as rows and pull ups, one typically commences with the concentric phase.

2. What is the purpose of the pause?

My reflections and experimentation with the pause led me to three primary benefits of the pause including:

- Negating of the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) contribution from the eccentric phase to augment the load potential in the concentric phase and its implication on muscle recruitment. g., the longer I held the pause on the chest in a bench press following the eccentric phase, the less weight I could lift, however there was a potential that the muscle could be working harder. This benefit is most apparent in pushing movements (movements that commence with the eccentric phase).

- Developing joint angle specific strength. E.g., the longer I held the pause on the chest in a row following the concentric phase, the less weight I could lift, however there was a potential that the muscle could be working harder at that joint angle, developing a joint-angle specific adaptation. This benefit is most apparent in pulling movements (movements that commence with the concentric phase).

- Developing technique, or joint angle specific co-ordination. When learning a new movement that involves technical cues, a slower speed of movement can assist with the learning process. Using the pause to contribute to slowing the movement down and allowing the athlete time to refocus on the subsequent body position associated with the upcoming contraction phase is valuable for this learning. E.g., at the bottom of a squat, I teach a certain management of the pelvis position, a concept I have published since the late 1990s yet one of the few to be embraced. To optimize the learning of this pelvic control and associated torso and limb relationship management, a pause is critical.

3. When should I pause?

There are two pause opportunities in a repetition:

- At the end of the eccentric phase and before the concentric phase.

- At the end of the concentric phase and before the eccentric phase.

Pause i. impacts the role of the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) in a way that Pause ii. does not. Pause ii. has since been promoted for its potential in energy recovery. However, I believe this is a very simplistic approach and fails to consider the cost implication of holding load in a static position, even if a biomechanically conductive position. My approach was to treat the pause equal at both ends.

4. How long should I pause for?

In relation to the duration of the pause I had simply concluded that the longer you paused, the harder it was to do the lift. Typically, I would advocate a pause duration between 0 and 4 seconds. I did not seek to quantify the duration of the pause. Now I don’t pretend to be a scientist. I have consistently said let the sports scientists come along in the future and give greater clarity to my theories. Ironically a few years later science did just that in relation to the impact of the pause.[5]

…My intuition has since been supported by science, especially the work of Australian strength researcher Greg Wilson, whose studies included a study that showed that the elastic energy from the eccentric phase continues to contribute to or augment the concentric power up until the length of pause equals or exceeds four (4) seconds (in the bench press at least).[6]

I don’t believe it is coincidence that the researcher who a few years later gave validity to my hypothesis (at least as it relates to bench pressing) was also a competitive powerlifter!

A point I want to clarify here is that Wilson’s research at that time related only to the competitive bench press, not any other lifts. This is another area that I believe has been poorly dealt with in publications since I promoted Wilson’s research – especially with those who use the ‘open book’ method of publishing (open a book and copy some of the contents, then publish the copy as their own).

For example, one publication claimed Wilsons research showed ‘that it took a 4 second pause before we eliminated the stretch-shortening effect. So, anything less than a four second pause still involves the use of momentum.’

No reference was made about any given exercise. Had this publication been based on original writing’, perhaps the ‘author’ may have read the original research and had a better understanding of what Wilson’s research said.

5. What happens if I vary the pause?

After recognizing and respecting the overlooked critical nature of the pause, the question was what happens when I vary the pause and when does it apply?

A number of training principles guide this decision:

- Specificity

- Variety

- Periodization

i Specificity: My thinking respected the dominant paradigms in the respective and opposing fields -bodybuilding and power sports. From a specificity perspective, I would use longer pausers for hypertrophy and learning, and shorter pauses for maximal load and explosive power.

2, Variety: However, there is a role in the application of the pause for what many would consider non-specific training. This is no different than any other program design variables – one is not compelled to be ‘specific’ all the time. In fact, additional training benefits come from variety.

The following is an example of this as applied to repetition range variety.

Variation may also give unexpected adaptations from repetitions. A trainee pursuing hypertrophy, after spending considerable time training in classic hypertrophy brackets (e.g., 8-12) may experience further significant hypertrophy when changing to a higher or lower rep bracket. Whilst this appears to contradict the above table, it shows that variety alone can accelerate gains. Note this applies in both strength (neural) and size (metabolic) training. The message is clear – irrespective of the specific goal, training in too narrow a rep bracket may not be as effective as alternating or mixing with different rep brackets. The key is not which reps to use, rather how much time to spend in each different rep bracket.[7]

3. Periodization: The fundamental principles of periodization recognize the value and need for change throughout a training year (horizontal integration) and throughout a career (vertical integration). For example, an athlete may commence their training year in the General Preparatory Phase (GPP) with less specificity in the pause and move towards greater specificity in the pause duration as their Competitive Phase (CP) approaches. Also, as an athlete advances in their level of qualifications over the years, the athlete may spend less time in non-specific pauses and more time in more specific pause duration combinations.

What happens when you vary the Speed of Movement (SOM)?

When choosing my early speed of movement combinations, I was relying on experience and intuition. There were no quantifiably measured training effects from specific speed of movement combinations, which is no surprise because at the time I developed the Speed of Movement concept during the mid 1980s’ there was no reference I could find in literature on this subject.

I typically used longer duration combinations for hypertrophy and learning technique, and shorter duration combinations for developing maximal strength and explosive power.

These generalizations are summarized in the following table:

The speed of movement combinations suited to various strength training methods. [8]

| Eccentric Speed/Time

(seconds) |

Pause Speed/Time

(seconds) |

Concentric Speed/Time

(seconds) |

Training Methods Most Suited to these Speed Combinations |

Examples of SOM Combinations |

| very slow and controlled |

long |

slow and controlled |

stability/control & general fitness; metabolic-end hypertrophy;

strength endurance |

8:0:4

6:1:3

4:2:1

3:1:3 |

| slow controlled |

medium |

fast/attempt to be fast |

general fitness; metabolic-end hypertrophy;

strength endurance |

3:2:1

|

| medium controlled |

short |

fast/attempt to be fast |

neural-end hypertrophy; metabolic-end max. strength; strength endurance |

3:1:1

2:1:1 |

| fast controlled |

nil |

fast/attempt to be fast |

neural-end maximal strength;

explosive power; strength endurance |

2:0:1

1:0:1 |

| fast |

nil |

fast/attempt to be fast |

explosive power;

quickness/SSC;

strength endurance |

10*

*0*

* |

How did I choose to communicate Speed of Movement (SOM)?

My primary focus was coming up with a solution to communicate with the athletes I trained exactly what Speed of Movement (SOM) I wanted them to use. I needed a simple yet effective way to achieve this:

To communicate how fast or slow I wanted an athlete to move the load in strength training, I developed a numbering system in the 80’s. [9]

By the mid 1980’s I had developed a system of denoting and communicating speed of movement in strength training that involved a simple numbering system. [10]

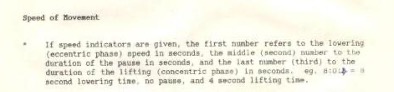

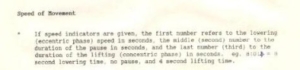

I settled on a three-digit method:

There are three numbers e.g., 3:1:1. All the numbers refer to seconds. The first number relates to the eccentric phase. The second or middle number to the pause or isometric contraction duration between the eccentric and concentric contraction. The third number refers to the concentric phase.

The fact that the first number always refers to the eccentric contraction can cause some confusion in the trainee as a percentage of strength exercises commence with the concentric contraction, especially the pulling movements such as the chin ups. However, once they become familiar with the system it works excellently. In brief, most pushing movements commence with the eccentric contraction, and most pulling movements commence with the concentric contraction.[11]

I also responded to the criticisms of my timing system in my 1998 book How to Write Strength Training Programs: [12]

- The first criticism regarded the confusion allegedly caused because I say the first number refers to the eccentric, even when the movement doesn’t commence with an eccentric contraction.

- The second criticism I addressed was about how ‘hard’ it is to count reps and monitor speed of movement.

Around 2010, twenty plus years after publishing the three-digit timing system, I read ‘new’ criticism. Ironically, the person leading the criticism below is a person who chose to teach this concept in a variety of publication over an extended period of time, unreferenced of course, except for the first time they published in, in line with what seems to be an industry protocol – reference it once and you have no need to apply referencing again.

I think the use of the three digit formula is partly to blame…[13].…the idea of controlling rep speed is vital. You have to do some kind of tempo prescription. I think the idea of using numbers was based on an over-reaction…[14]

Now heading towards forty years since I developed this concept, the criticisms continue.

In the past, we used this numerical system regularly to communicate tempo; however, we no longer use that method because it isn’t an effective way to communicate how the rep should always be performed.[15]

Time Under Tension (TUT) was such a popular idea for a long time. Here’s why it’s actually useless and what you should consider instead…[16]

As to the specifics of how I chose to communicate the three-digit timing system, I wrote this statement in 1987:

If speed indicators are given, the first number refers to the lowering (eccentric phase) speed in seconds, the middle (second) number to the duration of the pause in seconds, and the last number (third) to the duration of the lifting (concentric phase) in seconds. e.g. 8:0:4 = 8 second lowering time, no pause, and 4 second lifting time. [17]

And repeated it in countless publications since, such as the below example:

There are three numbers e.g. 3:1:1. All the numbers refer to seconds. The first number relates to the eccentric phase. The second or middle number to the pause or isometric contraction duration between the eccentric and concentric contraction. The third number refers to the concentric phase. [18]

I also provided guidelines clarifying expectations when the number ‘1’ appeared last, or when even faster movement was expected in the program design:

Additionally, when the number one does appear as the third number, the power athlete must have it reinforced – this means to try and go fast! This is rarely done. And when the asterisk (*) is used – it must look fast![19]

The first time – and last time – I observed this explanation published by other authors applying appropriate credit was by Charles Poliquin in 1997, over a decade after I had developed it:

Tempo, the speed of your lift, is always expressed in three digits, a formula refined by Ian King, Australia‘s leading strength coach. The first digit is the lowering (negative) portion, the middle digit the pause (isometric) phase, the third digit the return (positive) movement. Using the Front Squat example below, 3 refers to the three seconds it should take the lifter to squat down; 2 refers to a two-second pause at the bottom; 1 refers to the one second it should take the lifter to return to the start. X is used to denote “as fast as possible. [20]

In the 1980s and early 1990s, in both publication and in programs, I would place a colon or hyphen between the numbers. Considering I was handwriting the training programs for each athlete in the 1980s, it was an effort I will not forget! During the 1990s I morphed this into writing three numbers with no punctuation, more due to time efficiency than anything else. The variation used in unreferenced and uncredited publications indicates which decade of my publishing they are copying.

How and why was Time Under Tension (TUT) developed?

I coined the term ‘Time Under Tension’ (TUT) also in the 1980s. It was not needed as a communication for athletes. However, it was relevant to coach education.

TUT is not a synonym for speed of movement. It is a term used to measure the impact of the speed of movement – i.e., how long were the muscles under tension of the load/lift.

The application of my three-digit timing system made it possible to measure the duration of reps and sets to ascertain where they sat in the TUT table. In fact, without this system, this concept – TUT – would not have been very measurable.

The time from the start to the end of a set I called the ‘time under tension’ (TUT).[21]

This term has gone on to become not only popular but an accepted commonly used term in strength training.

Here’s how I describe TUT:

Time under tension (TUT) refers to the time that the muscle is working continuously. This is usually measured in seconds and refers mainly to the duration of tension within a set, although can be calculated as total time under tension in the workout. Time under tension is associated with metabolic adaptations from strength training, and is believed to be highly correlated with hypertrophy training. For example, a higher number of reps as are used in hypertrophy training, have an inherently higher time under tension (all things being equal) than a lower number of reps as typically used in neural strength training. [22]

The following provides working guidelines for the application of the TUT concept in strength training program design:

The following table shows a guideline for the training methods and benefits associated with varying time under tension. As is evident there is a degree of overlap between time ranges.[23]

Common interpretation of time under tension (TUT).[24]

| TUT |

Dominant Training Effect |

| 1-20 seconds |

Speed strength/maximal strength |

| 20-40 seconds |

Maximal strength/hypertrophy |

| 40-70 seconds |

Hypertrophy/muscle endurance |

Guideline for time under tension and associated training methods and adaptations. [25]

| Time under tension for set (seconds) |

Dominant Training Effect |

Training Methods and Adaptations |

| 1-20 secs |

N

E

U

|

Quickness / SSC

Explosive power

Neural-end maximal strength (relative strength) |

| 20-40 secs |

R

A

L

|

Metabolic-end maximal strength (absolute strength)

Neural-end hypertrophy |

| 40-70 |

M

E

T

A

|

General strength/metabolic-end hypertrophy

Stability/control & general fitness |

| >70 |

B

O

L

I

C

|

Stability/control & general fitness

Muscle endurance |

TUT was never suggested to be a science per se, rather a guideline. One day the scientists will have their say for those who seek ‘research’ approval. Nor was TUT developed to be taught to the end user. It was a professional-level concept aimed at providing some degree of quantification and categorization of the impact of combinations of Speed of Movement on training adaptation.

I am intrigued by the embracement of TUT in academic literature. This concept is referred to in so many articles, yet the expectations of appropriate, professional referencing are not met.

What was the publishing timeline of SOM and TUT?

I started using my three-digit timing system in program design with athletes in the mid-1980s. In the initial years I would verbally explain it to them to help them interpret their written programs. Keeping in mind that the individualized training program I gave to individual between 1980 and 1989 were hand-written, therefore access to printed documents was not as easy as it has been since the advent of the Information Age in 1989.

The next phase of communication with the athlete about SOM and the three-digit timing system was a printed document, kept loose-leaf in their training diaries. This worked reasonably well with the training diaries that I began producing in 1987[26] for athlete.

In about 1988 I began integrating this printed document into their training diaries.

The first commercial artifact I made available to the broader public was the 1989 edition of the training diary, however sales were by word of mouth, not marketed.

I had no desire or intention to market or expose the concept. Unlike the ‘modern-day’ strength coach, my focus was exclusively on giving athletes in my care a performance advantage and sharing proprietary concepts with others was not fitting with that vision.

This presented a challenge when I began to receive requests to publish training programs. I was not accustomed to writing programs with SOM guidance, so I had to choose between providing what I considered a sub-standard training program for publishing by excluding SOM, or including SOM and providing excellence, at risk of exposing the performance advantage.

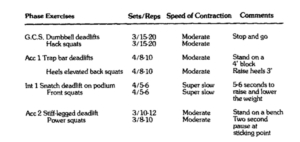

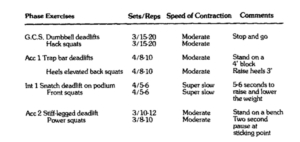

I chose a compromise – I submitted the programs for publishing with SOM guidelines in them but intentionally avoided any additional attention to this unique and proprietary concept. You can see examples of this, published and presented in Canada[27] [28] and the USA[29] [30] [31] [32] from the early 1990s onwards.

It was not until 1998 [33], over a decade after I began applying the concept, that I published more openly about it. The reason this occurred included:

- I have a multiple decade tradition of choosing not to publish on an innovation prior to a decade of testing and refinement.

- I increased my focus on coach education and this coincided with that move.

- The concept was being ‘leaked’ by a certain individual.

Let me be very clear – there were several colleagues who were exposed to the three-digit timing system during the second half of the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s. However, in that time there was only one whose modus operandi was to identify excellent, but little know training concepts typically found outside of North America and publish them.

The approach typically used was to publish them in the first instance giving recognition to the original source but claiming to have modified, and from then on drop the referencing to the origin. This strategy was attempted on the three-digit timing system, however perhaps unlike other original thought providers, my response resulted in a backing off from that approach, and they reverted back to more honest recognition of the source.

Tempo refers to the speed of a lift and can be expressed in a three-digit formula developed by Ian King, one of Australia’s most accomplished strength coaches.[34]

The first time I have found a publication by this individual using my three-digit timing system in program design was in 1997, over a decade after I developed the system.[35]

“It’s always expressed in three digits, a formula refined by Ian King, Australia’s leading strength coach…” [36]

Until then, the programs provided by this coach – either in public domain or in service to athletes – did not contain any digit-timing system. In fact, they did not recognize the pause between eccentric and concentric contractions at all.

However, to this coach’s credit, independent from my works as evidenced by their 1988 article, [37] they were aware of the value of varying repetition speed. However, this was in the absence of any awareness of the role of the pause between eccentric and concentric contractions, and in the absence of any digit timing system. Instead, words were used to communicate the indented speed. (See table below from this 1988 article). [38]

Providing further clarification about the intent and use of SOM and TUT

In 1998 I published content including the following with the intent of providing clarity about SOM and TUT. There had been an over-reaction to the concept, and more (slower reps, longer duration TUT) was being popularized as better:

Where I believe most get it wrong is this…the system never came with a user manual. The number one use of this system I believe is this. For those concerned about power, rate of force development, I do not recommend using anything less than a fast or attempted to be fast concentric contraction for some 80-90% of total training time.

A lack of awareness of the ‘need for speed’ (attempted acceleration) in the concentric phase in the power athlete may result in an adaptation to a non-specific rate of force development. This is the same non-effective and perhaps detrimental training effect that occurred when athletes first started using strength training and used the bodybuilding methods. A total lack of awareness of the need for a fast/attempted to be fast concentric contraction. Therefore, the power athlete cannot afford to spend more than 10-20 % (as a generalization) of their total strength training time using number greater than 1 as the third number. Additionally, when the number one does appear as the third number, the power athlete must have it reinforced – this means to try and go fast! This is rarely done. And when the asterisk (*) is used – it must look fast!

Note that …. programs as published in most popular media are for bodybuilders. Slower concentric times are used – and this is okay for bodybuilders…Great for hypertrophy, but non-specific to rate of force development. Use sparingly with the power athlete. Spend most of the time reinforcing ‘speed’!

The second most common error is for the program writer to compile a sequence of numbers which, when combined with the reps written, result in a time under tension that is not specific to their intended training outcome e.g. 421 x 10 reps (=70 sec) for maximal strength. This is an easy error to make and simply requires first understanding training effects as they are related to total time under tension, and then analyzing the program before it is given out.

The major groups of speed combinations I use are as follows (see Table 53). You may note that only one out of five (or 20%) of the combinations use a deliberately slow concentric phase.

Table 53 – The major groups of speed of movement combinations in strength training.

| Eccentric Speed/Time |

Pause Speed/Time |

Concentric Speed/Time |

| Very slow and controlled |

Long |

Slow and controlled |

| Slow controlled |

Medium |

Fast/attempt to be fast |

| Medium controlled |

Short |

Fast/attempt to be fast |

| Fast controlled |

Nil |

Fast/attempt to be fast |

| Fast |

Nil |

Fast/attempt to be fast |

The advent of the four-digit system

Following my 1998 ‘user-guide’ about the three-digit system, Charles Poliquin began publishing a four-digit system:

“…I now use a four digit system which is a refinement of a three digit system developed by my Australian colleague Ian King….” [39]

In my response to this ‘refinement of my system’ I wrote:

More recently some have added a fourth number to my three number speed description. This fourth number describes the pause time between the end of the concentric and the start of the eccentric phase. My initial numbering system inferred this pause to be the same as the pause between the end of the eccentric and the start of the concentric phase. There is technical merit to the addition of this fourth number, but I am not convinced that the average athlete or even program designer understands the rationale behind differentiating between the two pauses…. [40]

Note that the four-digit approach arrived nearly 15 years after I commenced using the three-digit system.

Perhaps my expectations are too high assuming that such a time gap would have provided more clarity about the subject. Even so-called ‘industry experts’ struggle with accurate interpretation.

Poliquin preferred a three-number system, while King preferred a four-number system…[41]

The industry response to SOM and TUT

It is interesting to note that after the publishing of SOM in Australia, Canada and the US between 1986 and 1996, there was limited uptake of the SOM and TUT concept and method.

For example, as an insight into lay media trends of the time, a program published in Men’s Fitness in 1997, there was no reference to SOM. [42]

This is not, in my opinion, an exception, rather than the rule. Take Dietmar Schmidtbleicher’s accumulation and intensification approach to strength periodization. [43] This method was proposed by the West German strength researcher in the at least the early 1980’s and further promoted by Canadian strength coach Poliquin including in his 1988[44] NSCA article.

It was only when this concept was published in populist lay-person publications that even physical preparation coaches began aware of and adopting the concepts. Again, I refer to the strength training program in the 1997 Issue of Men’s Fitness – not a single reference to this training method.

However, the awareness of these concepts changed after they were shared through lay publications, such the internet bodybuilding magazine t-mag (as they were known then), and books targeting the end-user such as Poliquin’s 1997 book[45]:

T: A lot of people don’t know this, but you pretty much invented tempo prescriptions, right? (Note: In case you don’t know, tempo prescriptions are those numbers like 211 you see beside most of the exercises listed in T-mag training articles.)

Ian: Definitely. That is my baby….

T: How did you come up with this idea?

Ian: It was just one of those conclusions I’d reached from my involvement in sport. I knew there was a difference between when someone holds the bar on their chest or bounces it off. So, what I did is control the variable in the pause between the eccentric and the concentric. I created a method for communicating what speed I wanted them to use in each part of the lift. It was, of course, in the form of three digits with each digit representing a certain number of seconds.

I do need to give credit to Arthur Jones and Ellington Darden. They were probably the only people making references to the eccentric and concentric speeds. Some say Arthur only wanted to control tempo to protect his equipment, but I don’t know about that. I just put it into a user-friendly, easy to communicate form for the athlete and I respected the pause. Since then, science has validated that pause, but I created the method from intuition before science validated it. This is what I meant by not waiting on the research. [46]

The father of this numbering system, or at least the uncle, is Australian super coach Ian King. I call him the uncle of this practice because Ian doesn’t take full credit for the numbering system. Instead, he lists Arthur Jones and Ellington Darden as the first to attach numbers to training programs. However, Ian was the first to recognize the role of tempo, or speed of movement, in what’s known as the stretch shortening cycle.[47]

You may not know this, but Ian King invented modern tempo prescriptions, you know, those 311 or 302 numbers you see listed after exercises in most strength coaches’ training programs. Good thing too, since manipulating rep speed can lead to different lifting goals (hypertrophy, explosiveness, maximal strength, etc.)[48]

Lack of accurate attribution

It would seem perhaps only a minority seek to determine the origin of concepts. In relation to SOM and TUT, I rarely see the appropriate attribution. I suggest two possibilities for this – firstly, the post 2000 advent of the 4th digit to SOM. This is despite that author providing appropriate attribution:

“…I now use a four digit system which is a refinement of a three digit system developed by my Australian colleague Ian King….” [49]

Secondly, I suggest that there has been a concerted effort by certain individuals to disguise the origin of much of their published works.

For example, in 2006, an individual who has worked to position himself as an ‘industry leader’, and who has published my speed timing methods frequently in the absence of any credit, gave an account of the history of the concept, concluding with an alleged rumor that ‘some say it [speed timing system] came out of Australia’. Yet, in the same publication, this author claimed to have ‘read nearly everything there is to read in the field of strength and conditioning’.

This trend of factually incorrect referencing continues:

The late Charles Poliquin was the first to teach us about tempo, suggesting a three-digit formula to help coaches communicate how reps should be performed by their athletes (later refined to a four-digit formula)…[50]

I expect that ethical and well-researched authors and presenters will appropriately reference and credit the origin of SOM and TUT. They were developed to serve the end-user, not to gain approval from or impress colleagues.

Conclusion

I set out in the early 1980s to learn what was the best way to train, both for my athlete clients and for myself. That journey included a focus on the question of what the optimal speed of movement is. The conclusions I reached from the search led to the two concepts. Firstly, the creation of a Speed of Movement (SOM) concept for the end user, using a three-digit system to communicate that speed. Secondly, a Time Under Tension (TUT) concept with guidelines relative to desired training outcomes to guide program design for professionals.

At the outset there was no intention to develop a concept and methods to be marketed or used as a tool for self-promotion, as my SOM and TUT concept and methods have been used by some. Rather it was a personal journey to solve an existing challenge, with no intention of releasing in the short-term.

SOM and TUT were never intended to be ‘exact science’. I leave that to my academic colleagues to qualify the concept. There were intended as methods of communication and concepts to provide framework for training program design decisions.

The fact that some find criticism is of little interest or relevance. SOM and TUT are not created to be obligatory-use concepts, and therefore one can chose to use them or not.

If your training results or those of your clients have or are being enhanced by your application of SOM and TUT concepts, they are serving in the manner intended.

——

NB. Want to dive deeper int SOM and TUT? Check the KSI Short Course – Time Under Tension – Exploding the Myths!

References

[1] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), Speed of Movement, p. 115

[2] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), Speed of Movement, King Sports International Publishing, p. 123

[3] King, I., 1999, Get Buffed! (Book), King Sports International Publishing, p. 68.

[4] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), p. 123

[5] Wilson, G.J., Elliott, B.C., and Wood, J.A., 1991, The effect on performance of imposing a delay during a stretch-shorten cycle movement, Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 23(3):364-70

[6] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), King Sports International Publishing, p. 123

[7] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), King Sports International Publishing, p. 93

[8] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), Speed of Movement, King Sports International Publishing, p. 126

[9] King, I., 1999, Get Buffed!™, Ch 12 – What speed of movement should I use?, p. 61-67

[10] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), Speed of Movement, p. 123

[11] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), Speed of Movement, p. 124

[12] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), Speed of Movement, p. 124

[13] xxxx, 2005, The Evil Scot: An interview by Chris Shugart, T-mag.com

[14] xxxx, and xxxx, 2009, Program Design Bible

[15] xxxx and xxxx, 2020, Secrets to Successful Program Design, Human Kinetics

[16] https://www.skillbasedfitness.com/its-time-to-forget-about-time-under-tension-tut/

[17] King, I., 1987 (1st Ed; 4th Ed 1990), Training Diary

[18] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), Speed of Movement, p. 123

[19] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), Speed of Movement, p. 123

[20] Poliqin, C., 1997, The Poliquin Principles, Science of Tempo, p. 25

[21] King, I., 1999, Get Buffed!, King Sports Publishing, Brisbane, Australia, p. 61

[22] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs, p. 129-131

[23] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs, p. 129-131

[24] King, I., 1999, Get Buffed!™, p. 61-52

[25] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs, p. 129-131

[26] King, I., 1987, Athlete Training Diary, 1st Edition (subsequent editions in 1988, 1989 and 1990). (Book)

[27] King, I., and Poliquin, C., 1991, Strength training for Alpine Skiing, Level 3 coach education seminar for the Canadian Association of Coaching Whistler Canada.

[28] King, I., 1993, Plyometric Training: In Perspective (Part 3), Science Periodical on Research and Technology in Sport, 14(2), Canada. (Article)

[29] King, I., 1992, Strength training and conditioning for rugby, Presentation at the 1992 NSCA National Convention, 18-20 June 1992, Philadelphia, PA, USA. (Presentation)

[30] King, I., 1996, The 12 Week Beginning Program Combining Strength Training and Jump Training for Long Term Development – Part 1, Performance Conditioning for Volleyball, Vol. (3):4, p. 4-5. (Article)

[31] King, I., 1996, The 12 Week Intermediate Program Combining Strength Training and Jump Training for Long Term Development – Part 2, Performance Conditioning for Volleyball, Vol. (3):5, p. 4-5. (Article)

[32] King, I., 1996, The 12 Week Advanced Program Combining Strength Training and Jump Training for Long Term Development – Part 3, Performance Conditioning for Volleyball, Vol. (3):9, p. 2-3. (Article)

[33] King, I., 1998, How to Write Strength Training Programs: A Practical Guide, King Sports Publishing, Brisbane, Aust. (Book)

[34] Poliquin, C., 2000, Current Trends in Strength Training – A reference manual, Tempo, p. 41

[35] Poliqin, C., 1997, The Poliquin Principles, Science of Tempo, p. 25

[36] Poliqin, C., 1997, The Poliquin Principles, Science of Tempo, p. 25

[37] Poliquin, 1988, Five steps to increasing the effectiveness of your strength program, NSCA, Vol 10(3):34-39.

[38] Poliquin, C., 1988, Five steps to increasing the effectiveness of your strength training program, NSCA J 10(3):34.

[39] Poliquin, C.,1999, Modern Trends in Strength Training, (draft)

[40] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (book), Speed of Movement, p. 124

[41] Robertson, M., 2010, Old school tempo training for more muscle, t-nation.com, 26 April 2010.

[42] xxxx, and xxxx, 1997, Three‐phase Weight Training Program, Men’s Fitness, Dec 1997

[43] Schmidtbleicher, D., Maximalkraft und Bewegungsschnelligkeit, Limpert Verlag, Bad Homgurg, 1980.

[44] Poliquin C. Five steps to increasing the effectiveness of your strength training program. NSCA J. 1988; 10: 34‐39.

[45] Poliqin, C., 1997, The Poliquin Principles

[46] King, I., 2000, in Shugart, C., Meet The Press – Coach of coaches: An interview with Ian King, 29 Dec 2000, t-mag.com

[47] Louma, TC and King, I., 1999, 4 Seconds to More Productive Workouts, Fri, May 21

[48] Shugart, C., 2001, The Ian King Cheat Sheets, Part 1 – T-mag.com

[49] Poliquin, C.,2000, Modern Trends in Strength Training

[50] xxxx, and xxxx, 2020, Secrets to Successful Program Design, Human Kinetics