Lines of Movement – The Origin and Intent

During the 1980s I began to research methods of categorizing strength exercises. By the end of this decade I had developed a concept I called ‘Lines of Movement’. After trialling this method for about ten years, I released details of this and other methods I had developed for categorizing exercises. I structure this organization under the umbrella concept of ‘Family Trees of Exercises’. I then expand into ‘Lines of Movement’. Then I divide exercises based on the number of limbs and joints involved.

These methods go far beyond simple organization – they allowed me to develop my methods of analyzing balance in strength training program design. I believe these innovations are highly effective tools available to guide a person designing a program to create optimal balance and reduce injury potential.

I began my first public teaching of these concepts in 1998 with the following statement:

That’s a concept I am sure you have never heard before because this is the first time I have really spoken about it. [1]

I began teaching the concept of ‘Line of Movement’ during the late 1980s. For example, in my 1989 presentation titled ‘5 Steps to Improved Resistance Training’[2] I wrote:

However it was not until 1998 that I chose to expand publicly on my innovations in this area: [3]

Family Trees of Exercise

The Family Tree concept is the foundation of my categorization, as taught below:

The following shows a breakdown of the body into major muscle groups/lines of movement, and then into examples of exercises. It is what I call ‘the family trees of exercise’. Use this to assess balance in your exercise selection. [4]

The first time I expanded fully on this concept was in a 1998 seminar:

After many years I have decided that there is two family trees in lower body exercises – one where the quad dominates, and one where the hip dominates. When I say hip I mean the posterior chain muscle groups – the hip extensors; which are gluteals, hamstrings, and lower back – they’re your hip extensors. And I believe this – the head of the family in the quad dominant exercises is the squat. That’s the head of the family. And there are 101 lead-up exercises to it and there’s a few on after it as well. But the core exercise for the quad dominant group is the squat. It’s the most likely used exercise in that group for the majority of people.

The hip dominant exercises – the father of the hip dominant tree is the deadlift – which when done correctly would be the most common exercise of that group. There are lead-in exercises, and there are advanced exercises from it.

So I build my family tree around the squat and I build my family tree around the deadlift. And I balance them up. In general, for every squat exercise or every quad dominant exercise I show in that week a hip dominant exercise in that week. And what do most people do in their program designs – they would do two quad dominant exercises for every hip dominant exercise. What is the most common imbalance that occurs in the lower body?

….To balance the athlete I work on a ratio of 1 to 1 of hip and quad dominant – in general. And I can assure you – most programs you’ll see are 2 to 1 – quad and hip.

That’s a concept I’m sure you’ll have never heard before because this is the first time I have spoken about it. [7]

In the following I discuss exercise options within each Family Tree:

….[hip flexion] Perhaps the long term staple of this family tree has been the straight or bent knee leg lifts whilst hanging from a chin bar…. Alternatively, I have devised many lower level movements so that this family tree can be given appropriate attention [9]

…[quad dominant] I therefore chose to use the squat as the ‘head’ of the quad dominant family tree… Take the squat (quad dominant) and the deadlift (head of hip dominant family tree). [10]

The squat is what I refer to as the ‘head’ of the quad dominant ‘family tree’…[11]

The deadlift is what I refer to as the ‘head’ of the hip dominant ‘family tree’ …[12]

The ‘head’ of the vertical pulling family tree is the chin up or similar. [13]

The chin up is what I refer to as the ‘head’ of the vertical pulling ‘family tree’. [14]

I spoke about Family Trees and my subsequent exercise category, Lines of Movement, in a number of different publications in the late 1990s:

I’m going to start working with exercises that I call come from the hip dominant family tree. Some of them are fairly unusual. But the aim of them is to balance the muscle development and the strength development with exercises more commonly done with the quadriceps.[15]

Lines of Movement

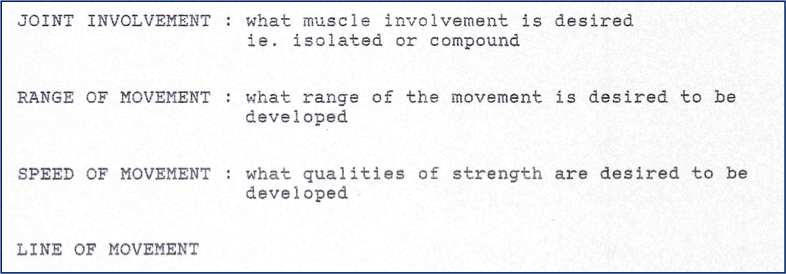

I first expanded in writing on the Lines of Movement concept in my 1998 ‘How to Write Strength Training Programs’ book: [8]

My first step is to create the following three sections:

- Upper body.

- Trunk.

- Lower body.

I then divide these three into the following:

1. Upper body

- Pushing.

- Pulling.

- Rotation.

2. Trunk

- Flexion.

- Extension.

- Rotation.

3. Lower Body

- Quad dominant (exercises that prioritize the quadriceps e.g. the squat and all its variations).

- Hip dominant (exercises that prioritize the hamstrings, gluteals, and lower back (e.g. the dead lift and all its variations).

- Rotation.

My next division is as follows, and takes into account lines of movement (i.e. vertical and horizontal. Technically speaking, the vertical plane should be called the frontal plane, but more relate to vertical)… [17]

Up until I released these concepts in the late 1990s, the strength training industry relied solely on the division of the body into muscles groups when designing or analyzing a strength training program.

Before Ian popped up from Down Under, most coaches said to train all the muscles of the legs in one session and use the most efficient exercises. That means squatting and deadlifting on the same day. Problem — As effective as these big mass builders are, they’re also very fatiguing and really sap your energy levels. If you start your workout with squats, your deadlifts will suffer and vice versa. [18]

The following is a sample list, not in any order, of the major muscle groups of the body that I published in 2000: [19]

A sample list of muscle groups, not in any order. [20]

_______________________________________________

abdominals

lower back

hip dominant (e.g. deadlift and its variations)

quad dominant (e.g. squats and its variations)

vertical pulling (i.e. scapula depressors e.g. chin ups)

vertical pushing (i.e. arm abduction e.g. shoulder press)

horizontal pulling (i.e. scapula retractors e.g. rows)

horizontal pushing (i.e. horizontal flexion e.g. bench press)

biceps

triceps

plantar flexors (calves) / dorsi flexors

forearm extension/flexion

________________________________________________

The following is another sample list, not in any order of importance, of the major muscle groups of the body and the ‘new terms’ I used to describe them, published in 2000. This list also clarifies the core strength movements associated:[21]

Table 1 – The twelve major muscle groups.

| Street Name | Anatomical Name | My Terms | Core Movements |

| Chest | Pectorals | Horizontal push | Bench press |

| No name! | Scapula retractors | Horizontal pull | Row |

| Shoulders | Deltoids | Vertical push | Shoulder press |

| Upper back | Lats | Vertical pull | Chin ups |

| Legs | Quads/hamstrings | Quad dominant | Squats |

| Butt | Gluteals | Hip dominant | Deadlift |

| Lower back | Spinal erectors | Back extensions | |

| Stomach | Abdomen | Trunk and hip flexors | Sit ups and knee ups |

| Lower leg | Calf | Calf press | |

| Upper arm | Bicep and tricep | Arm curls/extensions | |

| Lower arm | Forearm flexors/extensors | Wrist curls/extensions | |

| Traps(upper) | Trapezius | Shrugs |

After applying the conventional muscle group methods for many years, I had come to the conclusion that they did not adequately respect the overlap of muscles used in the different days of strength training, nor did it provide adequate insurance against imbalanced programs.

This injury prevention motive for creating this concept was reinforced in my earlier writings:

To simplify and ensure balance in upper body program design and training, I have divided the upper body movements generally speaking into four…..[22]

Muscle imbalance

Historically the focus in lower body strength training has been on the quads, and quadricep dominant exercises such as the squat. This has been OK for say bodybuilders, whose worst-case scenario is to have poor posterior leg muscle development. Even in track and field you will find authors admitting that during the 70’s the focus in power development in sprinters etc. was via leg extension as opposed to hip extension. If you take this fault in program design and training into strength training for athletes in general, the price can be a lot higher. It is my belief that an imbalance between quad dominant and hip dominant exercises where quad dominance is superior results in a significantly higher incidence of injury and a detraction from performance.[23]

At the time of developing this concept (the late 1980s) the only references in the industry were to ‘quad dominant’ (a physical therapist term) and push-pull (a term used in strength circles).

There was no reference to ‘hip dominant’, nor was there any recognition to the differentiation of the vertical and horizontal planes available in upper body movements.

So I developed, tested, refined and ultimately shared my concepts by 1998 and in the years that followed:

Now, a little additional clarification before I go on. I refer to muscles or workouts that are predominantly anterior thigh as being quad dominant, and those that are predominantly posterior thigh as being hip dominant. The following is a hip dominant routine that balances out the previous quad dominant routine. [24]

Initially appropriate recognition was given, for example:

To help you understand how to divide and balance out your training, Ian came up with a list of major muscle groups that reflects their function:

Horizontal pulling (row)

Horizontal pushing (bench press)

Vertical pulling (chin-up)

Vertical pushing (shoulder press)

Hip dominant (deadlifts)

Quad dominant (squats)

Ian has a few other categories for abs, lower back, calves, and arms, but the ones above are main muscle groups you need to worry about. Based on this list, you need to be doing vertical as well as horizontal pushing and you need to be doing the same number of sets for each and keep the rep ranges equal where appropriate.

Let me give you an example of how this list can help you. Before Ian provided this simple list, I did almost nothing but chin-up variations for back training. Sure, I did rows occasionally, but not very often as compared to chins. This was an imbalance. Now I do just as many sets of horizontal pulling as I do vertical pulling and it’s really helped my back development. [25]

And this:

My favorite four-day configuration is one Ian King uses in his more advanced workouts, which you can find on t-nation.com. I use his terminology to describe them:

Horizontal push/pull: …

Hip-dominant: ….

Vertical push/pull: …

Quad-dominant:….[26]

For simplicity’s sake, let’s use Ian King’s terminology and call them ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’ pulling.[27]

The unreferenced and un-credited use of Lines of Movement

From about 2005 onwards, the number of ‘author’s publishing my original works without appropriate referencing or and credits resulted in a dilution of the quality of the concepts, and the awareness of the origin. In my opinion this original desire by these authors to take credit for the concepts resulted in later publishing by ‘authors’ whose education lacked the teachings of the origin and intent of the concepts.

In the case of one ‘author’ who has created a niche market in the area of this and related topics, I have not found a single reference or credit to the source during the decade post 1999. Ironically this ‘author’ instigated a mass walk out of a seminar I conducted in the north-east of America where I was teaching these very concepts – alleging the content was terrible.

It is difficult to reconcile claims such as made the statement below from this ‘author’.

“I have read nearly everything there is to read in the field of strength and conditioning….”[28]

Either this claim is significantly embellished, or alternatively they choose to suppress the origin of the concept. Neither option presents a positive role model of ethical, professional behavior, for future generations.

I note also there has also been a trend in some instances from 2005 onwards (seven years after I first publicly released the concept and nearly two decades after I created it) to substituting one word in my model – the word ‘knee’ replacing the word ‘quad’.

In fact, these authors now publish more widely than I do on my concept, without any reference to its origin, and may have succeeded in leading the masses to conclude this is the model.

I note that only ethical and well-read ‘authors’ reference the source.

Using Lines of Movement in program design

I used my Lines of Movement concept to illustrate program design breakdown and progressions. A number of examples of this are found below. Prior to my publishing this technique, there was no such method of presentation.

Apart from the obvious advantages of analyzing and discussing program design via the use of Lines of Movement, the method I innovated to present program design as shown in the example below allows a person to illustrate or refer to Lines of Movement / muscle groups without needing to name the specific exercise.

An example of a 3/wk ’semi-total body’ split routine. This split requires less of your time and allows more time for muscle recovery than a standard total body workout. [29]

| Monday (A) | Wednesday (B) | Friday (C) |

| Quad dominant (e.g. squat) | Horizontal push (e.g. bench) | Hip dominant (e.g. deadlift) |

| Lower back (e.g. good morning) | Horizontal pull (e.g. row) | Vertical push (e.g. shoulder press) |

| Vertical pull (e.g. chins) | Triceps | Biceps |

| Forearms | Calves | Upper traps |

An example of a 4/wk split routine. This split requires more of your time but also allows more time on muscle group. [30]

| Monday (A) | Tuesday (B) | Thursday (C) | Friday (D) |

| Horizontal push (e.g. bench press) | Hip dominant (e.g. deadlift) | Vertical pull (e.g. chin up) | Quad dominant (e.g. squat) |

| Horizontal pull (e.g. row) | Hip dominant (e.g. good morning) | Vertical push (e.g. shoulder press) | Quad dominant (e.g. lunge) |

| Triceps | Upper trap | Biceps | Calf |

Unlike those who have copied my works in this regard, I did not abandon reference to or respect of the subject of muscle groups. In fact, I would typically interchange between terms as a synonym. This is also well illustrated in the above table from my 1998 book ‘How to write strength training programs’. [31]

Conclusion

The Lines of Movement Concept was released 21 years ago, in 1998, and was quickly embraced by authors who in the first instance recognized and credited the source. It within a few years from that certain authors began using this concept frequently in their publications, unreferenced. Professions with higher integrity protect the copyrights of innovators. Apparently not this industry.

Writers who have done their research and are ethical in their values will appropriately and consistent with acceptable professional referencing guidelines will display referencing and crediting when using these concepts in their publications.

[1] King, I., 1998, How to Write Strength Training Programs (Book)

[2] King, I., 1989, 5 Steps to Improved Resistance Training, Weights Workout ’89, Workshop Tour

[3] King, I., 1998, Strength Specialization Series (DVD), Disc 3, approx. 1hr 03m 00sec in.

[4] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (Book), p. 38

[5] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (Book), p. 38

[6] King, I., 2000, How to teach strength training exercises (Book), p. 41

[7] King, I., 1998, Strength Specialization Series (DVD), Disc 3, approx. 1hr 06m 00sec

[8] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (Book), p. 39

[9] King, I., 2000, How to teach strength training exercises (Book), p. 54

[10] King, I., 2000, How to teach strength training exercises (Book), p. 99

[11] King, I., 2000, How to teach strength training exercises (Book), p. 102

[12] King, I., 2000, How to teach strength training exercises (Book), p. 108

[13] King, I., 2000, How to teach strength training exercises (Book), p. 115

[14] King, I., 2000, How to teach strength training exercises (Book), p. 118

[15] King, I., 1999, Ian Kings Killer Leg Exercises’, t-mag.com

[16] King, I., 1998, Strength Specialization Series (DVD), Disc 3, approx. 1hr 03m 00sec

[17] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (Book), p. 40

[18] Shugart, C., 2001, The Ian King Cheat Sheets, Part 1 A quick and dirty look at all the cool stuff Ian King has taught us so far, t-mag.com, 24 August 2001

[19] King, I., 2000, How to Teach Strength Training Exercises (Book)

[20] King, I., 2000, How to Teach Strength Training Exercises (Book)

[21] King, I., 2000, So You Want To Start A Weight Training Program? Part 4: Muscle group allocation and Exercise selection, Peakhealth.net August, 21 2000

[22] King, I., 2000, How to Teach Strength Training Exercises, (Book), p. 114

[23] King, I., 2000, How to Teach Strength Training Exercises (Book), p. 99

[24] King, 1999, Limping into October Pt. 2 (now showing as ‘Hardcore Leg Training – Part 2’)

T-mag.com, Fri, Sep 24, 1999

[25] Shugart, Chris, 2001, The Ian King Cheat Sheets, Part 1 – A quick and dirty look at all the cool stuff Ian King has taught us so far, Fri, Aug 24, 2001, T-mag.com

[26] Schuler, L., 2006, The New Rules, Ch. 3 – The building blocks of muscle, p. 42, (2009 paperback version) Penguin Publishing, New York.

[27] Schuler, L., 2006, The New Rules of Lifting, p. 149, Penguin Publishing, New York.

[28] Authors name withheld to protect the message. A 2005 quote.

[29] King, I., 1999, Get Buffed!, Chapter 4 – How often should I train? (Book), p. 18

[30] King, I., 1999, Get Buffed!, Chapter 4 – How often should I train? (Book), p. 18

[31] King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs (Book), p. 25