The glutes are over-rated

Prior to the publishing of the Lines of Movement concept in the late 1990s no-one gave a ‘rats-arse’ (an Australian colloquialism) about the glutes. At least no one outside of a therapy clinic. Twenty years later the glutes have been given the same prime time rating as the Swis ball got in the late 1990s.

I know the message in this article will be as popular as most of my comments at the peak of the popularity of any trend (i.e. not very!) so I am just going to rip the band aid off.

If you really want to help people, if you want to make significant and more complete changes to the way a human functions, you have got to get past this narrow focus on the glutes. The glutes are over-rated and you don’t need to be part of this.

Before we go further lets appreciate the short history of ‘glute focus’. As I said, prior to the Lines of Movement concept (you know, those categories of movement/exercises that a few post 2000 authors got amnesia about when it came time to referencing) there was zero focus, discussion or exercises on or for the glutes – outside of selected physical therapy clinics. The legs were the legs.

Check out the program I use for analysis in Volume 3 of Ian King’s Guide to Strength Training – How to Transfer. You can see very quickly there is no focus or attention on the glutes. This program was published in a populist mainstream bodybuilding magazine about 6 months prior to the 1998 publication of Vol 1 of Ian King’s Guide to Strength Training – How to Write Strength Training Programs, in which the world got it’s first real view of the Lines of Movement concept.

So what happened post 2000? I guess a few people felt caught out and wanted to compensate. And compensate they did. Before we get into some of these over-compensation examples, allow me to expand on where I see the glutes in the bigger picture.

Yes, the glutes and glute activation are important. No, I am contradicting myself! Keep reading.

They were and still are a big part of the pre-activation drill concept (I called this control drills) I began sharing late 1990. They were part of the reason I expanded the range of unilateral single leg (compound and single joint) exercises when I realized that the Quad Dominant range was far greater than the Hip Dominant range. This is why I took a few exercises out of the aerobic class of the 1980s and 1990s, a few from physical therapy, and made up a few more.

Then why I am so critical of the light now being shone on the glutes?

For a few key reasons.

Firstly, from my perspective, and from the way I design and teach others to design strength training programs, the glutes act as a ‘force couple’ with the abdominals, in their role in determining the positioning of the pelvis. Now the abdominals have less role in hip and thigh extension than the glutes but at least equal role in injury prevention as it relates the pelvic stability.

Now I know the debate of pelvis stability and I don’t really want to open that can of worms. I seek to wrap that discussion for now with this comment – a powerlifters competitive day at the office may involve 6 efforts of pelvis control, and who really gives a shit where the pelvis goes? They don’t and therefore, for now, I don’t. It can flap about like a ‘dunny house door in the wind’. (More traditional Australian colloquialisms!)

But athletes on a continuum from there onwards – athletes whose completion involves more than 6 reps of pelvis control e.g. an athlete who runs 30 kms in multiple directions on a field as part of their competitive day at the office – if you don’t give a shit about that – and by the way I see their programs looking like most of their strength coaches don’t – then you may as well take a 12 gauge to their lower extremities, because that would quicken the inevitable.

Yes, a bit dramatic – but I really tire of those who use powerlifting as their basis for athletic preparation. Powerlifting is a sport. It is not the basis of all other sports!

So if you want to muddy the waters about how the focus on certain abdominals muscles and or actions make you ‘weak’ – you need to stay in the powerlifting circle, because outside of that, the need to be able to run pain free for years to come is far more pressing than the ability to displace maximal external load 1 meter in a few very simple movements!

I suggest that this whole misguided discussion about abdominal contribution has singularly contributed to more lower extremity injuries in sports than…well, as equal, at least to the next factor.

The second additional factor that is overlooked is the length and tension of the quads. Of course many of you will want to say that stretching makes you weak, and really, do I need to go back and tell you to tell someone who cares?

Sadly, many coaches and athletes have been sucked into the vortex of ‘but it makes you weak’, when their future career, their income, their health, their legacy, is more dependent on their ability to remain pain free than their ability to perform some non-specific expression of strength immediately after performing some non-specific stretch, as is the basis of these studies!

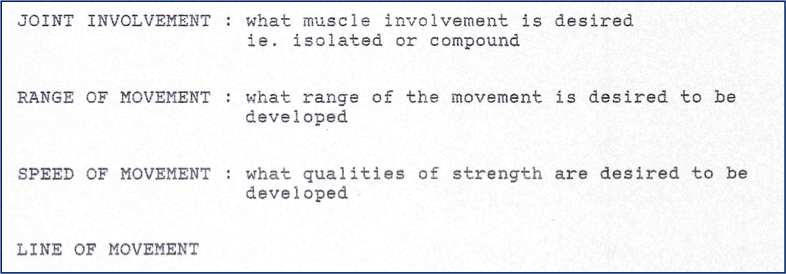

So let me put this simply and concisely – the health of the lower back, hips and lower extremities – relies on a discerned distribution of focus between:

- Length

- Tension

- Stability

Of the:

- Quads/hip flexors

- Abdominals

- Glutes

The way I see that, there are nine key focuses (3 x 3 = 9). NOT ONE!

Those of you who are familiar with my work will be familiar with this statement:

Muscles aren’t weak – they are inhibited!

Now if the concept was simpler, and more trendy and closer to Malcom Gladwell’s tipping point – then I am sure you would have read that multiple times by now in a functional training book or heard about it in a functional seminar already! But’s it not.

It’s not as a brain dead simple as many need to absorb, and it’s not currently popular and it sure as hell isn’t sexy.

But it’s not that difficult either!

Now the reason I raise the above point is this – you can bash the shit out of you glutes as much as you want – but if they are too long, too short or too tight – then they just won’t work anyway!!! It’s not that simple! But it’s not that difficult either – it’s a more holistic approach.

So what are the grounds for my suggestions that glutes are over-focused on in our industry currently? Here’s a real world example:

Question: A 15 year old female basketball player, who has talent to play at the next level, frequently has to take a game or two off (or play reduced minutes) due to knee pain. She has been diagnosed with bilateral chondromalacia patella.

She has come to you in the early off-season to try to get stronger and reduce the pain in her knees. Starting with an assessment, what do you do?

Answer:

1) The first thing we would do is to take the athlete through a [functional movement screen]

2) After this assessment we would more than likely confirm our suspicion of weakness in all of the lower body musculature with a large glute med deficit.

3) Next we would palpate the glute med for point tenderness. Our experience is that athletes with patella-femoral pain almost always have significant soft tissue inflammation in the glute medius.

4) I will make the assumption that all leg extensors are weak (quadriceps, glute,hamstrings) particularly the glute med and that there is a significant soft tissue component involving the glute med.

Note: The best description of the glute medius issue is that the glute medius is the muscular connection of the IT band connective tissue to the knee. Inability to stabilize with the glute med will result in knee pain that will exist at a conscious level and glute med pain….[1]

Here’s the scoreboard on this advice – the gluts were mentioned ten (10) times. The abds didn’t rate a mention. The quads / hips flexors earned one (1) mention.

Unbalanced? I suggest so.

Now what about modalities? Strengthening of the muscle got 7 mentions (6 glutes, 1 quads/hip flexors). Tension got four (4) (all Glutes) and length didn’t rate a mention.

Unbalanced? I suggest so.

In literal summary, this injury (bilateral chondromalacia patella ) rehabilitation and (therefore prevention) approach is that the condition was caused overwhelmingly (91%) by weak glutes (and this conclusion was reached by pushing on the glute to see if it was tender…), and would be solved predominantly (60%) by strengthening the glutes.

And the advice above, of course, was concluded with the obligatory promotion to buy a specific coloured band to perform that all-solving strength work. Hard to sell space on a mat when all they are doing is stretching with no other equipment….or a control drill with no equipment needed…

Now many would say – so what? That advice sounds right, because that’s what we do. In fact most do this, so go and stick it where the sun don’t shine Ian.

And of course you will get those spineless Internet trolls who will roll out the lovely adjectives I hope they don’t use when their grandmother is listening.

Which is fine by me. My goal is not to convince. Rather to give the opportunity and encouragement to those have this burning niggle in their mind that there is must be a better way, to find that better way.

Because quite simply, in my humble yet firm opinion, if the above example solution is where your commitment to excellence stops, I hope you never get to train a child, or a person who feels compelled to conform.

You can imagine what I think about those articles (marketing pieces) where the story is based on how some guru wrote a glute training program for them and it solved all their problems! It even cleaned the plaque on their teeth, and took out the trash. Okay so maybe I went to far with the add-ons. However you will find these articles, and they are not helping place the glutes in perspective, which is what I seek to do.

So let me sum up the key reasons I have shared for why I believe the current focus on the glutes is over-rating them.

- The glutes act as a ‘force couple’ with the abdominals, and therefore the abs should be getting equal attention.

- The length and tension of the quads impacts the functions of the glutes. If they are winning the battle against the force couple of the abs and gluts, – that is, if the pelvis is excessively anteriorly rotated as a result – and if as a result the gluts are not at an optimal length, the gluts are never going to be able to express optimal strength. No matter how much many exercises for the gluts you do.

Thirdly, I suspect a marketing factor –

- The glutes may have a higher ‘sexy currency’ currently than the abs. Perhaps because the focus on the gluts has a greater gender readership than a similarly narrow focus on abdominals (more females focused on the shape of their butt than whether they are running a six-pack).

The glutes are over-rated in the industry simply because certain other factors are under-rated. The solution provided lacks holism and is doomed for mediocrity, at least in everywhere other than in those miraculous ‘Guru X did a glute program for me and now I don’t need surgery’ articles….

Again, in conclusion I can only encourage you to reflect on this before buying into the current dominant trend that the glutes are the primary cause of all lower body ailments.

[1] Xxxx, 2006, Reference withheld to protect the message.